March 26, 2021

By Eduardo Cuevas

(For Hartnell College)

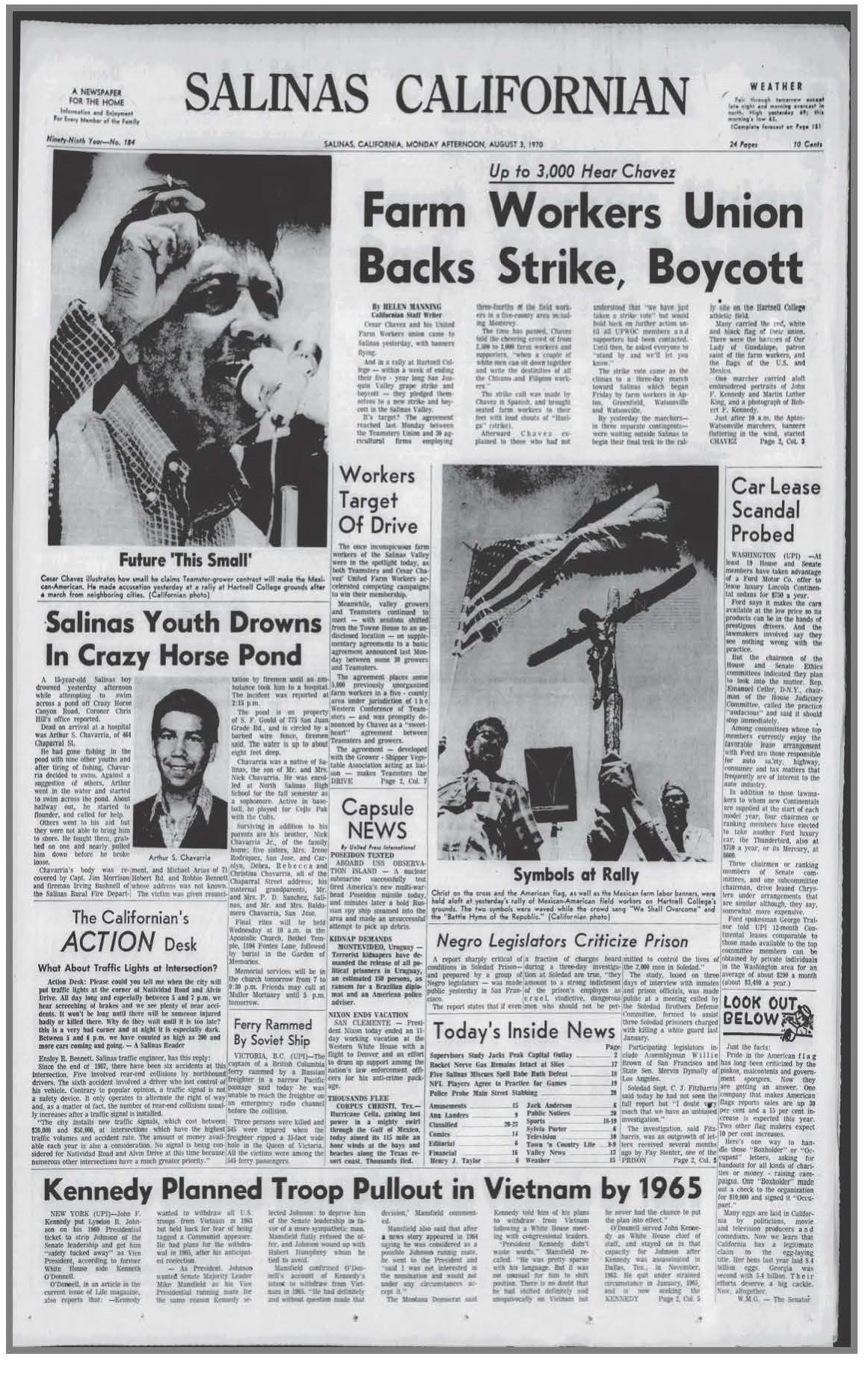

More than 50 years have passed since Monterey County Agricultural Commissioner Henry

Gonzales and 3,000 others watched Cesar Chavez lead a United Farm Workers rally at

Hartnell College, but Gonzales hasn’t forgotten what he saw and felt that day at age

15.

More than 50 years have passed since Monterey County Agricultural Commissioner Henry

Gonzales and 3,000 others watched Cesar Chavez lead a United Farm Workers rally at

Hartnell College, but Gonzales hasn’t forgotten what he saw and felt that day at age

15.

Gonzales listened on Aug. 2, 1970, as Chavez spoke from a makeshift stage at the edge of the Hartnell football field in Salinas, framing the UFW’s mission in starkly racial terms.

Referring to a new labor contract between Salinas Valley growers and the Teamsters Union, reached without UFW consent, Chavez said the time had passed “when a couple of white men can sit down together and write the destinies of the Chicano and Filipino workers,” according to an account in The Salinas Californian newspaper.

By then, as a student at Alisal High School, Gonzales had already spent three summers harvesting lettuce with his grandfather. Recalling his teenage mindset at the time, he said: “I’m just another Mexican. I’m going to be another Mexican farmworker. That’s all I wanted; that’s all I learned.”

But with the UFW’s historic chant of “Si se puede,” or “Yes we can,” Gonzales said, “I learned that if anybody else can do it, so can I, and I can do it better. That’s the attitude change.”

He graduated from Hartnell in 1980, earning an Associate of Science degree in Agricultural Mechanics, and went on to earn his bachelor’s degree from Fresno State University and an Executive Master’s degree from Golden Gate University in San Francisco.

Gonzales has been county ag commissioner since 2018, after holding the same office in Ventura County for the previous nine years.

Advent of UFW ‘Salad Bowl’ strike

The enormous rally at Hartnell was a pivotal moment in the history of farmworker rights. Less than a week before, the UFW had finally won the right to represent Filipino and Mexican farmworkers through a bitter five-year grape strike and boycott in the Central Valley.

As that victory catapulted the fledgling union from grapevines and dirt roads to nationwide awareness, the UFW organized a three-day march to Salinas to spur local activism. Separate groups marching from Watsonville, Hollister and Greenfield converged at the midpoint of Hartnell.

Several Chavez biographies quote Ray Tellis, a documentary filmmaker for the UFW, saying that Chavez’s speech at Hartnell was the most animated he had ever seen the UFW leader, who specifically called on the crowd to strike that day.

“The strike call was made by Chavez in Spanish,” wrote reporter Helen Manning in the next day’s Californian, “and it brought seated farm workers to their feet with loud shouts of ‘Huelga!’” or strike.

What became known as the Salad Bowl strike, considered the largest farm worker strike in United States history, officially began on Aug. 23 with a meeting at Hartnell of representatives of workers from 27 of the largest lettuce-producing ranches.

The strike brought Salinas Valley agribusiness to a standstill and helped make Chavez and his words a touchstone of pride and inspiration for generations of Mexican Americans.

On Labor Day 1970, the Citizens Committee for Agriculture — formed by growers and others opposed to the UFW’s efforts in the Salinas Valley — also met at Hartnell to rally some 2,500 to 3,000 supporters against the strike.

Committee chairman Bill Hitchcock said his group was trying “‘to back up our local people, to rebuild the mutual trust and good faith we knew until two weeks ago and to make the valley safe to work in once again,” according to The Californian’s reporting the next day.

The 1970 lettuce strike lasted seven months, ending with an agreement between the Teamsters and the UFW, reaffirming field workers’ right to organize. That December, Chavez was held for 21 days in the Monterey County Jail, less than a half-mile from Hartnell, where he received separate visits from both Coretta Scott King, widow of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., and Ethel Kennedy, widow of Sen. Robert F. Kennedy.

Tabera: ‘That was my first march’

The thousands gathered at Hartnell on Aug. 2 carried UFW banners, American and Mexican

flags and pictures of the Virgin of Guadalupe and Martin Luther King Jr.

The thousands gathered at Hartnell on Aug. 2 carried UFW banners, American and Mexican

flags and pictures of the Virgin of Guadalupe and Martin Luther King Jr.

There in the crowd was 16-year-old Phillip Tabera, a 1978 graduate of Hartnell who teaches Chicanx Studies at the college.

Tabera had briefly met Chavez not long before the rally as UFW leaders gathered in Salinas to finalize their plans.

On a Saturday morning in late July 1970, Tabera was outside his family’s east Salinas home, prepping his 1964 Mustang ready to cruise with friends when his mom told him he was wanted on the phone.

The call was from Manuel Olivas, a California Rural Legal Assistance investigator and Tabera’s mentor from the Mexican American Political Association. Olivas told Tabera to get down to his law office right away.

When he arrived, Olivas directed him to wait in an upstairs library. As he sat there, he heard commotion on the street below. Then the library doors slid open, and in walked a UFW group that included Chavez and his co-chair, Dolores Huerta, both of whom Tabera had heard of but never met.

With street maps spread out on the tables, the group planned what routes the three separate marches’ would take into Salinas.

“That was my first march,” said Tabera, who also attended Hartnell and was a longtime Salinas Union High School District trustee. “I never forgot that. Never. Practically every day after that I hung out with the [UFW] guys — with all the work they were doing.”

Rally energizes farmworker movement

During the rally at Hartnell, Marc Grossman, then a 20-year-old Watsonville organizer and later Chavez’s press aide, looked out over thousands of gathered marchers holding red UFW flags with a black eagle in the center. This, he imagined, was what it looked like when the Russian Bolsheviks entered Moscow after overthrowing Czar Nicholas II.

As Tabera remembers, the afternoon rally at Hartnell — held on a sunny, breezy Sunday — included a Catholic mass, out of respect for the religion shared by Filipino and Mexican farmworkers.

“The strike in Salinas was the first time that I really felt a movement,” said Marshall Ganz, an early director of organizing for the UFW and now a senior lecturer in the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

Ganz describes that weekend’s marches and the rally at Hartnell as a gamble, with scant investment of planning and resources from UFW headquarters in Delano. But in retrospect, he said, the event helped motivate farmworkers to organize, whether by forming UFW committees at agricultural companies or conducting grass-roots outreach within farm labor camps.

Ganz pointed to shared experiences of those days that ranged from the camaraderie of single men from Mexico working together on lettuce crews, to Mexican American strawberry-picking families from the La Posada farmworker camp in Salinas.

Hartnell’s football field — now the site of Building K (Merrill Hall) and the Child Development Center — was secured for the rally by a newly formed group for Mexican American students, a chapter of Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA). The Brown Berets, a Chicano group modeled after the Black Panthers and composed of many local community college students, provided security below the rally stage and at surrounding buildings.

Less than a year after serving in Vietnam as a Marine, Gonzales native John Macias helped coordinate these proceedings as head of Hartnell’s MEChA group.

“We have to be in specific positions to help do specific things,” said Macias, a retired Salinas High School principal. “You have to put the right people there.”

A moment of deep social change

At the time of the 1970 UFW rally at Hartnell, Salinas’ Mexican population had begun to grow rapidly. This was largely driven by braceros — Mexican guest workers brought by the United States government from 1942-64, often to segregated and substandard living and working conditions. They moved into burgeoning Mexican, Mexican American and Tejano communities.

The late UFW organizer Jessica Govea told Frank Bardacke, author of “In Trampling Out the Vintage: Cesar Chavez and the Two Souls of the United Farm Workers,” that Mexican workers in Salinas were different from the Mexican American farmworkers in Delano.

Govea considered the latter more “beaten down in the United States on so many forms, especially in school.” But in Salinas, she said, “They were very alive. There was an electricity, a vibrancy that was different from Delano.”

Citing U.S. Census data, Bardacke notes that the official population of Salinas more than doubled from 1960 to 1970, with the largest increases among residents with Spanish surnames.

At the same time, however, living conditions in Mexican communities remained dramatically below those occupied by whites.

“Nobody freaking helped us,” Tabera said, recalling a time when the city had no Mexican American teachers, elected officials or visible community leaders. Speaking Spanish was prohibited on school grounds.

The year 1970 was also when Hartnell had its first Chicana homecoming queen, Sally Pena, and Ben Anguiano would become the first trustee of color a year later.

By the time Tabera became active with the UFW in Salinas, his parents were afraid for his safety. His father told stories of violence against Mexicans in his native Texas, while his mother was a Teamster herself in a Salinas frozen-food business, having experienced violent strikes as a girl in the 1930s.

Tabera said his grandfather was a mutualista, belonging to a community-based mutual aid group for Mexicans. That grandfather knew braceros who were among the 32 who died in 1963 when a train hit a bus carrying 58 farmworkers outside Chualar, a tragedy that led to federal investigations of workers’ treatment in the Salinas Valley.

Ganz, of Harvard, said the Salinas strike of 1970-71 is historically significant as

part of a racial justice movement, not only as a union dispute. He compared the UFW’s

impact to the 1964 Summer of Freedom in Mississippi, during which he worked to register

African American voters despite violent oppression and state disenfranchisement.

Ganz, of Harvard, said the Salinas strike of 1970-71 is historically significant as

part of a racial justice movement, not only as a union dispute. He compared the UFW’s

impact to the 1964 Summer of Freedom in Mississippi, during which he worked to register

African American voters despite violent oppression and state disenfranchisement.

“It was never just about money; it was about basic dignity,” Ganz said of the UFW’s efforts in Salinas. “People will organize around injustice in a way that they don’t organize around inconvenience. It’s never just wages; it’s something deeper. And the arbitrary treatment, the favoritism, and this deep racial dimension was really an important piece.”

‘More than a union organizing movement’

Henry Gonzales recalls the dread he felt over the impending strike in August 1970. He wondered whether he’d be fired from his lettuce crew or get beaten for protesting. UFW lawyer Jerry Cohen appeared on The Californian’s front page in a hospital bed after he was attacked in a field outside of Salinas.

Nonetheless, Gonzales said he did his part by boycotting grocery stores outside of those located in east Salinas, standing with activists from the University of California, Berkeley, and others supportive of the farmworker movement.

By 1971, the UFW and the Teamsters agreed to represent workers, though many of the contracts gained would be lost years later.

Chavez organized another march to Salinas in 1979, beginning from San Francisco, that lasted 12 days and ultimately involved as many as 25,000 people. It ended on Aug. 11 with a rally at Sherwood School that was attended by Gov. Jerry Brown. The next day, the UFW held its constitutional convention inside the Hartnell gymnasium, attended by 248 delegates from four states.

The UFW’s power had diminished by the 1980s — partly from internal turmoil caused by the leader’s purges of key leadership. But out of change spurred in large part by the movement for farmworker rights, Salinas-area Latinos began to gain local political and social influence, taking Monterey County to court in 1991 for violations of the Voting Rights Act and eventually electing Latino candidates to local and state offices.

“It was more than a union organizing movement,” Gonzales said. “It was part of a social movement that led to many different changes — improvement for farmworkers and a sense of empowerment that led people to do more.”